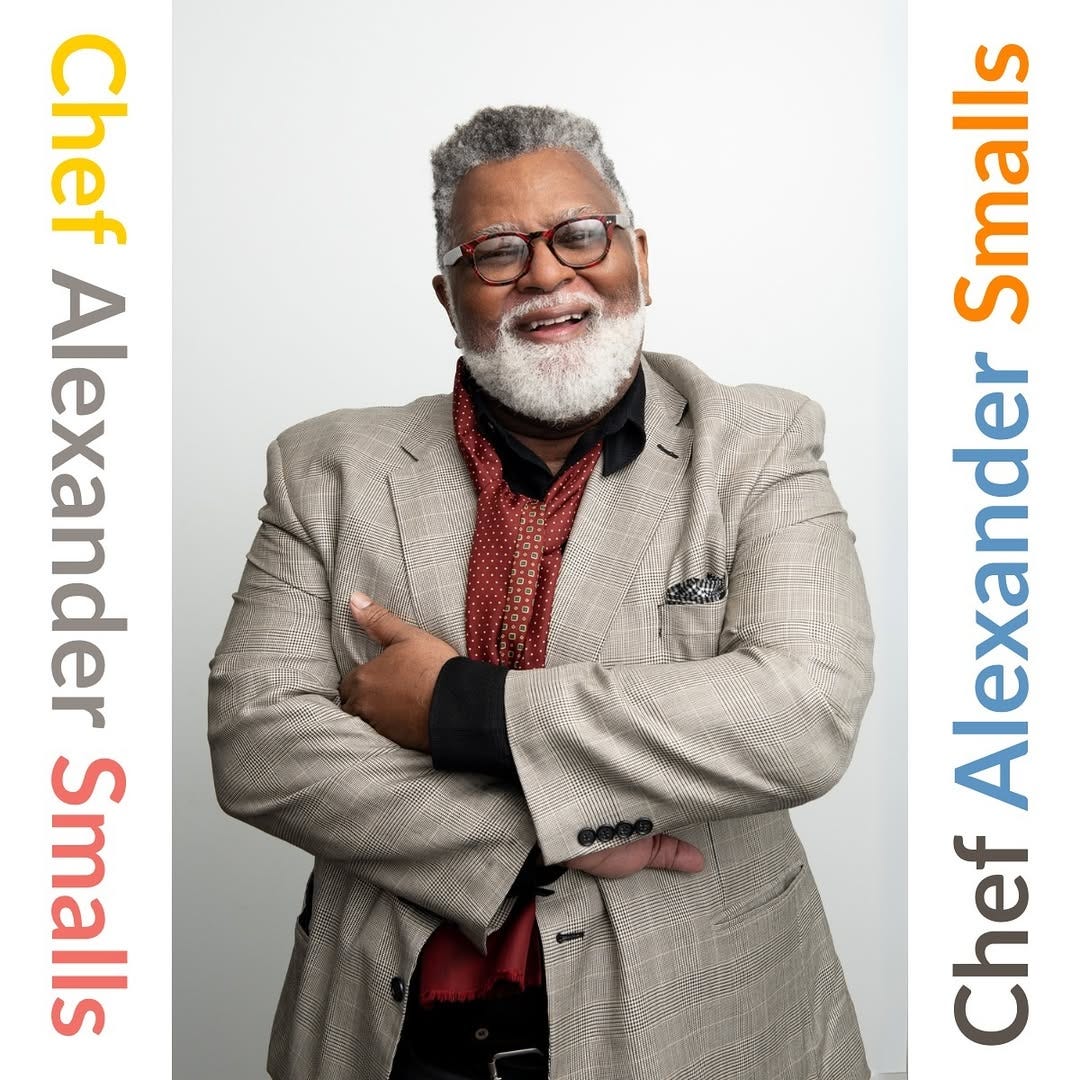

Order Up! A Conversation with Chef Alexander Smalls, multi-hyphenate Restaurateur, Opera Singer, & Author

From his grandfather’s garden to his own Harlem kitchen, Alexander reflects on food as memory, love, and cultural legacy.

It’s the first interview of the month, which means that this incredible full-length interview is available for all of our readers! One Potato is a reader-supported newsletter - paid subscribers have access to the full archive of Specials, Interviews, Recipes, and Community Voices for $5/month or $45/year.

Small Bites:

Back-to-school means back to basics: packing lunch, pitching in at dinner, and learning life skills that stick. The Kids Cook Real Food course helps kids gain confidence in the kitchen—while making your evenings a little easier.

👉 Check it out here.

Want help meal planning? Back to school = back to “what’s for dinner?” The Peas & Hoppy meal planning app makes that question way easier with 11 flexible recipes, a smart grocery list, and tips for real-life families.

👉 Try it free for 30 days - use code ONEPOTATO30

Chef, restaurateur, author, and opera singer Alexander Smalls shares the childhood kitchen stories, family recipes, and life lessons that shaped his journey

There are some people whose lives feel almost too big to fit into one story, and Chef Alexander Smalls is one of them. A Grammy- and Tony-winning opera singer turned chef, cookbook author, and cultural icon, he’s lived many lives, but the common thread has always been storytelling. Whether through music, through his NYC and then global restaurants, or through his award-winning cookbook Between Harlem and Heaven, Smalls has been dedicated to carrying forward legacy: of family, of community, of foodways that connect past to present.

In our conversation, Chef Alexander opens up not just about his career, but about the meals and memories that shaped him long before the spotlight. He shares what he learned tending his grandfather’s garden as a child, the simple dishes that hold his family’s history, and why passing down food traditions to the next generation is one of the most important things we can do as parents. For Chef Alexander, food has never just been about feeding people; it’s about telling the truth of who we are, where we’ve come from, and what we want to carry forward.

And while Chef Alexander isn’t a parent himself, his stories remind us how deeply childhood nourishment shapes who we become. The way a grandparent seasons a pot of beans or how a holiday table feels can ripple forward for generations. His reflections are a reminder that feeding children isn’t just about today’s dinner but about passing on love, memory, and identity through food.

A message from our friend & partner Katie Kimball, Kids Cook Real Food:

More Than Chores: Kitchen Lessons That Stick

Chef Alexander Smalls reminds us that food is more than just fuel—it’s family, memory, and legacy. And the best way to pass those traditions on? Get kids cooking right alongside you.

The Kids Cook Real Food eCourse, created by educator and mom Katie Kimball, helps kids learn real kitchen skills (beyond just following a recipe). From packing their own lunches to pitching in at dinner, kids gain confidence while parents get much-needed help during the busy back-to-school season.

👉 Explore Kids Cook Real Food courses, and start building your family’s food story together.

A Conversation with Chef Alexander Smalls

Introduce Yourself: My name is Alexander Smalls. I’m a chef, restaurateur, author, opera singer, and culinary activist. But really, at my core, I’ve always been a host.

From the time I was a boy, I noticed that the person holding the spoon, essentially the one making the food, was the engine of the family. They set the tone, they brought everyone together. That’s who I wanted to be.

Tell us about that childhood kitchen. What meals brought your family together, and who was the real “host” in your home growing up?

I grew up in the segregated South in the 1960s and 70s, so family was everything. My grandfather had a huge garden, and our homes were all clustered around it—his house on one side, my aunt and uncle on another, and ours on the third point of what I like to call a little “pyramid.”

I worked with him often in that garden, planting and harvesting food that we’d later eat together. He was what we called a “city farmer,” and the garden was his church. He also carried on the oral tradition of telling stories while we worked, keeping our history alive because so much of it was never written down. Particularly for enslaved Africans, food and storytelling were our currency; recipes and dishes were gifts we could give, and that persisted and was handed down. That connection—between food, memory, and survival—was central to my upbringing.

And then there was my mother, who I adored. I was always at her side in the kitchen. Between her cooking and my grandfather’s storytelling, I found myself right in the center of it all.

From the garden into the kitchen—what did that look like for your family? Was your grandfather also part of that process?

He absolutely was. My grandfather not only grew the vegetables but also raised livestock on land outside of town. I’d ride with him in his truck to feed them, even during slaughtering time. It was hard work, but he approached it with prayer and reverence, and that made an impression on me.

Cooking itself was very much a family affair. My Aunt Daisy and Uncle Joe were both chefs. Uncle Joe and his wife Laura, who was a classical pianist and my first piano teacher, they actually moved back from Harlem to South Carolina after I was born because they wanted to help raise me. They became my mentors, teaching me Shakespeare, playing opera records, introducing me to the Harlem Renaissance. Imagine: a little Black boy in a one-horse Southern town reciting Shakespeare in his mother’s rose garden! That exposure is what made me dream of becoming an opera star by age eight.

It terrified my parents—an entertainer was not the plan—but the greatest gift they gave me was that they never said “no”. Even when my choices led me into spaces where I was often the only Black person in the room, they encouraged me. They knew food and music were my anchors, and they trusted those passions would guide me.

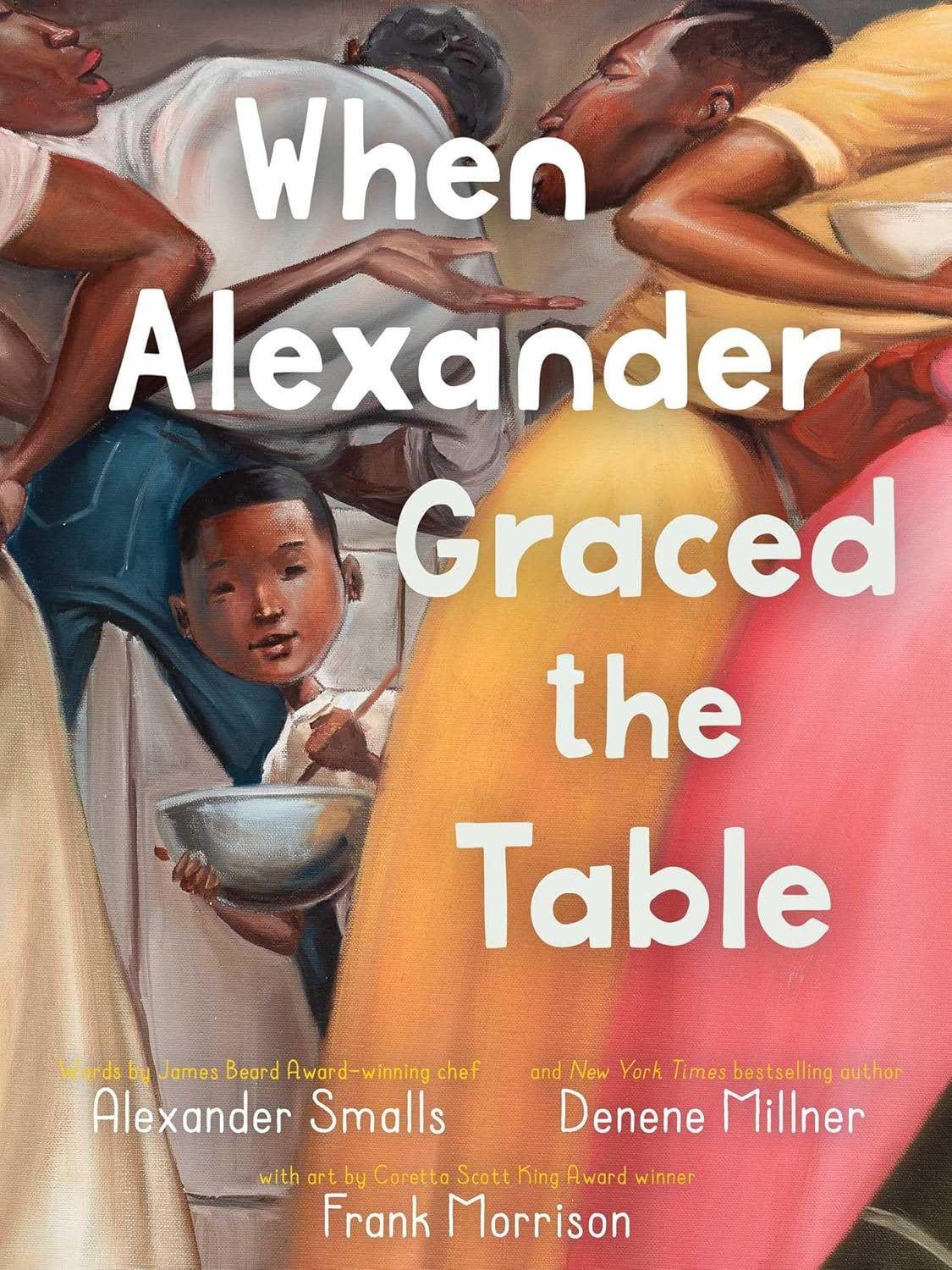

You’ve also written a children’s book, When Alexander Graced the Table. What inspired you to share your story in that way?

I’ve always felt childhood is the most important part of life: it’s where your values are formed and your dreams are sparked. I wanted to write a love letter to my parents and to that time in my life, while also encouraging kids to dream big and to help parents see the power they have in nurturing that. I was a happy, adventurous child, and all of that was encouraged. That’s the foundation of who I became, and I wanted to give that message back through the book.

Is there a recipe or dish that instantly takes you back to your parents’ and grandparents’ kitchen?

Two, actually. The first is pie—I’ve been making one since I was five years old. My mother would let me make one for the family and one just for me. I’d eat too much, feel sick, swear off pie for a week, and then… it was pie time again.

The other is hot dogs. My parents loved filet mignon, but they always cooked it until it was tough as shoes. So I’d ask for beans and franks or a hot dog instead. To this day, I still love them so much that every single one of my cookbooks includes a hot dog recipe. My New Year’s Eve tradition at home is champagne, with crispy leeks and crème fraîche on caviar. It’s pure joy.

You’ve spoken about the importance of creating spaces that honor Black culinary traditions. How do you see home kitchens carrying on that legacy?

It’s simple: we have to cook. Restaurants are wonderful, but it’s in the home kitchen where our stories and traditions live. A pound cake passed down from your grandmother, your aunt’s fried chicken, your family’s banana pudding—those dishes are cultural currency. They tell who we are. When we gather around a home-cooked meal, we’re not just eating. We’re preserving legacy, celebrating love, and giving our kids a foundation of belonging.

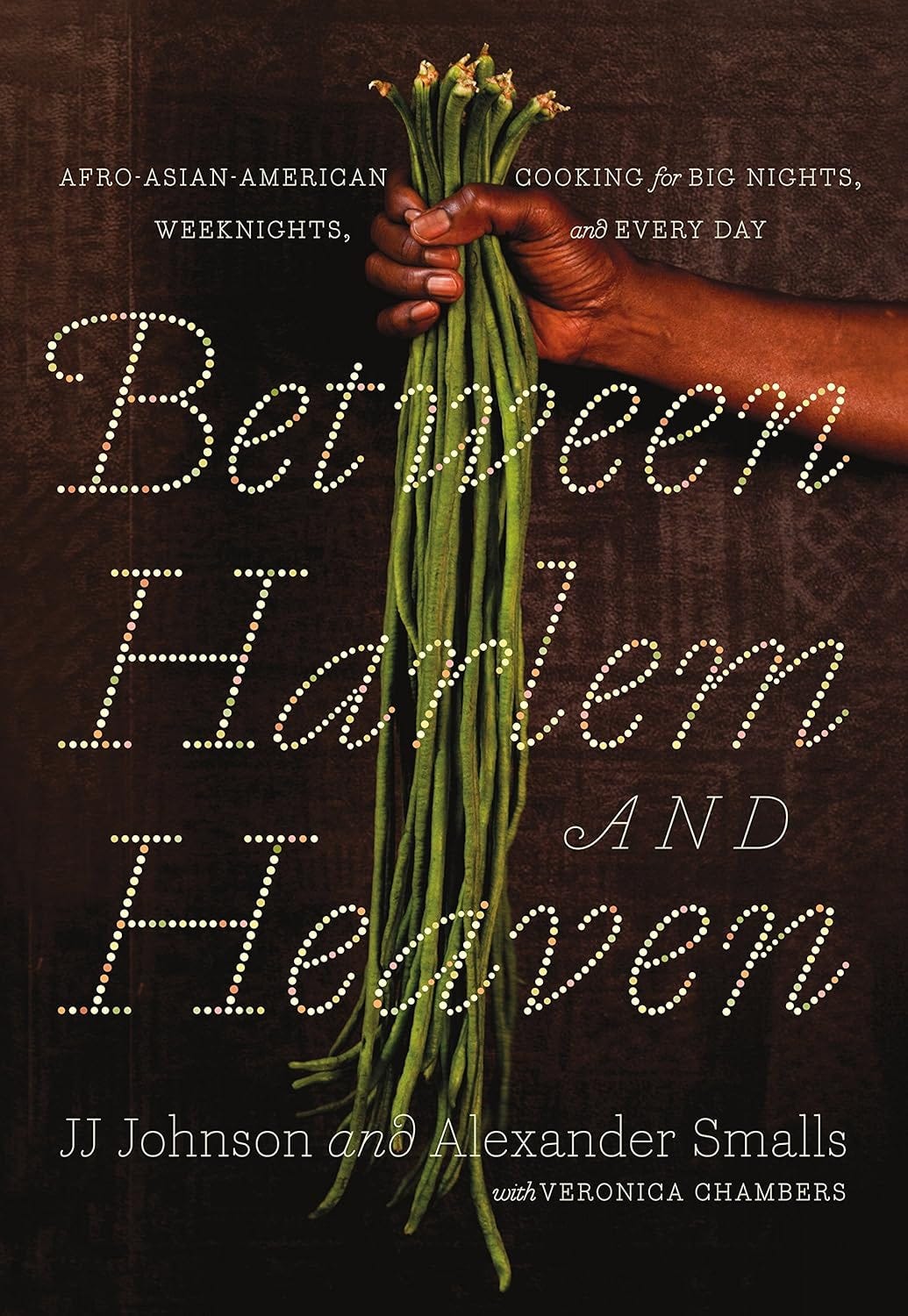

Your book, Between Harlem and Heaven, is such a celebration of the African diaspora through food. What do you hope readers would take from it?

My work focuses on how, through slavery, Africa changed the global culinary tradition. That book came out of a ten-year journey I took to trace African culinary traditions across continents. I wanted to understand how my grandfather’s Gullah Geechee roots connected to Africa and how enslaved people transformed global foodways.

For so long, our food was dismissed or demonized; for example, the world wanted me to believe that my grandmother’s pan brown gravy was “bad” compared to a French grandmother’s butter and heavy cream sauces. I rejected that. With Between Harlem and Heaven, I wanted to create representation at the table—to show that our food belongs in the global culinary conversation, not as an afterthought but as the main event.

Shifting gears to family tables. What’s your tip for getting kids to try new or unfamiliar foods?

Let them lead. Take them to the store and let them choose the vegetables that catch their eye—bright colors, interesting shapes. Bring them into the process: should we bake this? Sauté it? Steam it? When kids get to make choices, they build confidence and they’re more excited to taste the result.

It’s about listening to them, not just telling them what they “should” like. Food is a way to empower kids to trust their own voice.

If you had to pick one cooking skill every home cook should master, what would it be?

The one-pan dish. If you’ve got a good skillet, cast iron or something sturdy, you can do just about anything. Toss in fresh vegetables, keep them moving so they stay bright and crisp, season with herbs. Add shrimp or chicken if you like, maybe noodles or rice, and you’ve got dinner in minutes.

It’s simple, it’s flexible, and it teaches respect for ingredients. And it’s a great way to get kids in the kitchen because once they see how easy it is to turn a handful of things into a full meal, they’ll want to keep trying.